Why I WON’T Be Using Facebook’s New Reaction Buttons

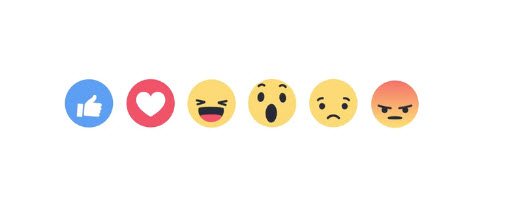

Facebook just rolled out 5 new “Reactions” to complement the platform’s ubiquitous “Like” button: Love, Haha, Wow, Sad, and Angry. Unfortunately, “Troubled” isn’t among them to capture my initial reaction to the new features.

So what’s wrong with more choice? After all, “Like” doesn’t even begin to capture our full range of emotions, so surely this gets us closer to reality, right?

I won’t argue with that part. In fact, the other problem with “Like” is that it, to this point, has represented the only form of social currency on Facebook. You have to post something “Like-able” in order to score points. People naturally filter themselves in public, but “Like” means that people filter themselves further by misrepresenting their range of personal experiences as mostly positive. It’s no surprise then that Facebook use has been tied to a number of negative mental health outcomes as people compare their own realities to the highlights of others (the article I linked to was co-written by an ASU colleague of mine who happened to work at Facebook for a bit).

So will expanding the reaction options lessen the negative outcomes tied to the “Like” button? Facebook wouldn’t have made such a big change affecting more than a billion users without a lot of testing and forethought, right? Of course not. You just have to remember that Facebook is a publicly traded advertising platform, not a public health service. Facebook is not optimizing for global wellness. They are optimizing for engagement to drive and increase ad revenue, to maximize shareholder returns. Your interests and Facebook’s interests aren’t all that aligned.

With that said, I’ll describe a few of what I think are some likely outcomes from this new set of reactions:

- More Facebook engagement. Those who wouldn’t have reacted at all to something now have a way to do so. Those who wouldn’t have posted something negative now have a way to generate social currency with the equivalent of a “Like.”

- Faster usage. Emoticons give people an easy-out, emotionally. Sometimes they express what words can’t. But here, I think they’ll just replace words and replace time spent thinking about what words to say. Less time spent reacting to content will increase the amount of things you react to rather than decrease the amount of time you use Facebook.

- More polarizing content. With new social currency driving behavior, you know that more users will post content to optimize for that currency by tapping into the emotions of the new reactions. All of a sudden, there’s more incentive to share the inflammatory, the heartbreaking, etc. This may mean that users and page owners start sharing a broader mixture of content, since they’ll have more to draw from in order to keep engagement high. But this mixture will be high on the emotional intensity scale. The “clickbait” tactics use to create “surprise and delight” stories will now be used for “shock and horror” and other exciting combos.

- Less feedback. When people aren’t forced to articulate their reactions in the form of words, then content producers can’t really get a true sense of the emotions they are producing. I think of the range of verbalized responses that can come from a good joke posted on Facebook. But now a lot more of that verbalization gets funneled into a large bucket called “Haha.” This introduces a lot more friction into the feedback loop, making it harder for a comedian, for example, to tell just how much people liked a joke. Those who would have clicked “Like” now click “Haha” and those who would have commented now click “Haha” too, so it makes it much harder to discriminate across the range of genuine reactions because they all get lumped together in a single click.

- Less empathy. This returns to the theme of the easy-out emoticon. I think there’s something healthy and worthwhile about having to process negative or difficult material — the kind that can’t be emotionally resolved with a “Like” button. When you remove the need to process by funneling people into simple emotional reaction buttons, you remove the same processing that produces genuine empathy toward others. I wonder whether some offline relationships and interactions may become more shallow over time as a result.

- Less action. The new reaction buttons enable new varieties of virtual “slacktivism.” Just as showing “token support” online for a cause alleviates peoples’ motivation to do something tangible like donate time or money, I fear that showing “token sympathy” for someone by way of a button click will have the same consequence. There will be cases in which someone who might have otherwise offered to bring a meal to a sick friend decides instead that their offering of a “Sad” click is supportive enough. I think Facebook cultivates a form of emotional entropy that leads people away from “doing,” not toward it.

So while I see a lot of broad support for the new forms of expression, I am also a little concerned about the implications over the long term. For me, the gains aren’t worth the offsetting damage to emotional growth and human connection. I want to struggle and grapple with how to respond (verbally or substantively) to anything that can’t simply be “Liked.” If reactions come easy, they aren’t worth much, and neither are the stories and people behind them.